- Home |

- Search Results |

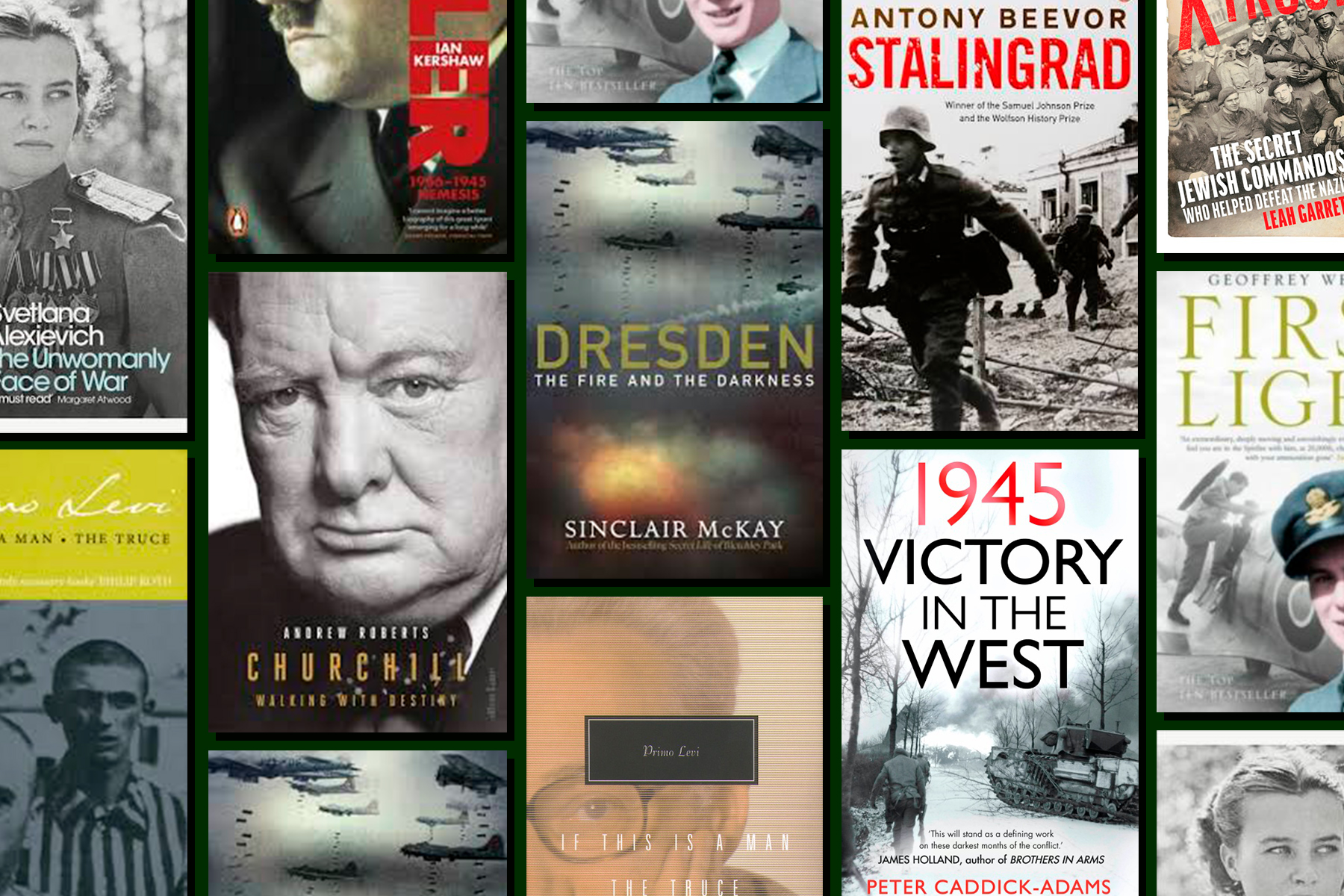

- The greatest books ever written about the Second World War

To call the Second World War merely a war is almost a misnomer; it was never just one war, but so many wars in one. Certainly, it was far too big, too vast and varied, to remember as a single event. The sheer volume of books about it are testament to that.

No war in history – except possibly the one that ended 20 years earlier – has inspired more literature. WWII has been seemingly endlessly written about, pored over, interpreted and re-interpreted – most recently, with the release of the film Oppenheimer, which takes place against the backdrop of the Second World War.

The film's release has caused a resurgence of interest in literature about WWII. But, with so many books to choose from, it can be hard to know where to start.

Mercifully, we’ve got the scope to help – and have rounded up the best non-fiction books ever written on the conflict.

Hitler 1936-1945: Nemesis by Ian Kershaw (1991)

To read this book is to ride shotgun through the mangled mind of a maniac – a mind so twisted, dark and terrifyingly pathetic that it demands a guide. Fortunately, Ian Kershaw has spent a lot of time there – and he knows the scenic route.

Far from the puffed-up political strongman that history remembers, Kershaw paints a portrait of an idle, tasteless, disillusioned loafer who got lucky. Kershaw’s examination of how a 'spoilt child turned into the would-be macho man' is unrivalled, not only in its breadth and depth, but in its richness of character. Here was a man, plagued by paranoia, Parkinson’s Disease and arteriosclerosis who had no firm ideas beyond a gut-deep hatred of Bolsheviks, poor social skills and a quite chronic case of donkey breath. And yet he convinced a nation that a brutal genocidal war was a good idea, and that he had the chops to take on the world.

This is a heavyweight biography from a world-champion historian. It remains undefeated in its category.

Inside the Centre by Ray Monk (2013)

This extensive biography of J. Robert Oppenheimer shines a unique light on one of the most contentious and influential figures of the period. As head of the Los Alamos Laboratory, Oppenheimer oversaw the efforts to beat the Nazis in creating the first nuclear bomb. But Inside the Centre delves deeper into the man called the 'father of the Bomb', uncovering Oppenheimer's complicated and fragile personality, and how the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings weighed on his conscience. This is a thorough investigation into a fascinating figure, and definitely worth a read.

'We are all worms,' Winston Churchill once told a friend. 'But I do believe that I am a glow worm.'

And glow he did. We all know the headlines – his rousing speeches play on a perpetual loop at the back of Britain’s national psyche – but Andrew Roberts’ exceptional biography gets further beneath the skin of the old bruiser than anyone – bar, perhaps, the man himself – has before.

The greatest challenge of writing a biography of Churchill is that Churchill has already done it inimitably (My Early Life, The World Crisis, The Second World War). But Roberts never falls into the punji hole of trying to out-Churchill Churchill. He writes with supreme authority, brio and no small amount of panache of Churchill’s exhilarating life, from his birth in 1874, to his death ninety years later. Nor does he pull his punches when it comes to Churchill’s many mistakes, either. Which is why Roberts’ tome earned the reputation of 'the best single-volume biography of Churchill yet written'.

If This Is a Man by Primo Levi (1947)

If you are to read one book about The Holocaust in your lifetime, let it be this. It is the most profound, haunting, and soul-churningly beautiful book I have ever read about the atrocity. I try to avoid bringing myself into these recommendations, but in this case I can’t help it: my copy reduced me to tears. Or, take it from Phillip Roth, who called it 'one of the century's truly necessary books.'

Primo Levi was a Jewish-Italian chemist and member of Italy’s anti-fascist resistance when he was arrested and herded to Auschwitz in 1944. If This Is a Man relives the horror of his experience.

If you’re looking for a historical investigation into the rise and appeal of Nazism, or an inquiry into the origins and nature of evil, look elsewhere. This is a guidebook to Hell. It’s a story of collective madness, sheer evil, incredible stupidity and cruelty, but also humanity, spirit, grit and luck. Buy two copies – you may need a spare.

X Troop by Leah Garrett (2021)

It might invoke Inglorious Basterds, but this isn’t fiction. Here, the real-life tale of Jewish refugees from Britain, sent to infiltrate and disrupt the Nazi war effort at every turn, is brought to vivid life by in-depth original research and interviews with the surviving members by author Leah Garrett.

Trained in counter-intelligence and advanced combat, these survivors – who lost families and homes to the Third Reich – became a unit known as X Troop, and their untold exploits, now published in full, illuminate a hitherto unknown story from an endlessly documented era.

The Unwomanly Face of War by Svetlana Alexievich (1985)

War is seldom told from a woman’s point of view. And yet, a million women fought for the Red Army during the Second World War. The Unwomanly Face of War tells their stories, in their words. Snipers, pilots, gunners, mothers and wives: Alexievich spoke to hundreds of former Soviet female fighters over a period of years in the 1970s and 1980s.

After decades of the war being remembered by 'men writing about men,' her goal was to give a voice to an ageing generation of women who’d been dismissed as storytellers and veterans, shattering the notion that war need be an ‘unwomanly’ affair.

In the author’s words, ‘“Women’s” war has its own colours, its own smells, its own lighting, and its own range of feelings. Its own words. There are no heroes and incredible feats, there are simply people who are busy doing inhumanly human things.’ It is a challenging read, namely because it is difficult to swallow in one go, but it would be hard to think of any book that feels more important, immersive and original. It was also one part of a body of work that earned its author a Nobel Prize in 2015.

On February 13th, 1945 at 10:03, British bombers unleashed a firestorm over Dresden. Some 25,000 people – mostly civilians – were incinerated or crushed by falling buildings. In some areas of the city, the fires sucked so much oxygen from the air that people suffocated to death.

Dresden, now, has become a byword for the immeasurable cruelty of war. But was it a legitimate military target, or was it a final, punitive act of mass murder in a war already won? McKay’s account of that awful day – and many on either side – is probably the most gripping and devastating of them all. It is certainly the most comprehensive.

He tells the human stories of survivors on the ground as well as the moral conflicts of the British and American attackers in the sky. But McKay is under no illusion: Dresden was an atrocity. Sizzling with heart, anger, and brooding intensity, this tells the story of a once-great city pulverised to ash. No other Dresden book beats it.

First Light: The Story of the Boy Who Became a Man in the War-Torn Skies Above Britain by Geoffrey Wellum (2002)

It took Geoffrey Wellum 35 years to turn his notebooks into a narrative. And a further quarter-century to get them published. The result is best described as one of the most engaging personal accounts of aerial warfare ever written.

Wellum was 17 when he joined the RAF in 1939, and 18 when he was posted to 92 Squadron. That’s where he first encountered a Spitfire. At first, he was clueless about the ways of combat, ravaged by fear and self-doubt. He found himself flying several sorties a day. He fought the Battle of Britain, and against German bombers during the Blitz. He fought at day and at night, from the skies above Kent to those above France. By 21, he was a battle-hardened flying ace who’d shot down as many enemies as friends he’d lost. In the end, life-or-death stress of mortal combat began to take its toll, as he succumbed to battle fatigue.

It is a beautifully written story of fear and friendship, bravery, bullets and, ultimately, burn out. You can practically smell the oil and gun smoke in the ink.

Stalingrad by Antony Beevor (1998)

Many terrible battles were fought during the Second World War, but none come close to the savage four-month German Soviet battle of Stalingrad. It was all shades of awful. For context, consider that the Allied death toll in Normandy reached an appalling 10,000. At Stalingrad, it was closer to a million.

The staggering scale, the megalomania, the depravity, the crushing absurdity, and the unspeakable carnage that took place across Stalingrad from August 1942 to February 1943 is exquisitely captured in Beevor’s definitive history of the event.

He magnificently combines a novelist’s verve with an academic’s rigor as he recounts, step by step, how the battle unfolded in all its miserable awfulness. In doing that, Beevor has created an unforgettable diorama of one of the most savage battlefields in history, one of wholesale death, indignity and waste.

1945: Victory in the West by Peter Caddick-Adams (2022)

By March 1945, victory was within the Allied grasp – yet, the last 100 days of the Second World War would prove to be some of the very hardest. In this latest tome from Peter Caddick-Adams, the writer, broadcaster, and former lecturer in Military and Security Studies at the UK Defence Academy – not to mention a PhD-holding expert in multiple war zones – zooms in on the brutal last days of the Allied forces, as exhausted they slogged on through villages and towns, fighting bloody battles and finding, near its end, the barbarities of Hitler’s death camps.

Meticulously researched but compellingly told, 1945: Victory in the West is a new masterwork with a strong claim to canonical status in the World War Two library.

Beyond the Wall by Katja Hoyer (2023)

While not technically a book about the Second World War, Beyond the Wall addresses the legacy of the war on Europe; specifically, how it led to the creation of the socialist state of East Germany.

Far from the Cold War caricature of desolation often painted by the West, historian Katja Hoyer finds that despite the hardship and oppression, East Germany was home to a rich political and cultural landscape. She traces the history of the German Democratic Republic from the exiled German Marxists who created it, through to the building of the Berlin Wall, the prosperity of the 1970s, and the rocky foundations of socialism in the mid-1980s.

This unique story, which was an instant Sunday Times bestseller, compiles interviews, letters and records, to give a clear picture of the Germany that nobody really knows about: the one beyond the Wall.